Resistance to antibiotics is rising but the business model for developing new antibiotic drugs is broken. Could CARB-X, the world’s largest public-private partnership devoted to antibacterial research and development, be the answer? Patrick Kingsland finds out more from CARB-X executive director Kevin Outterson.

Patrick Kingsland November 22, 2017

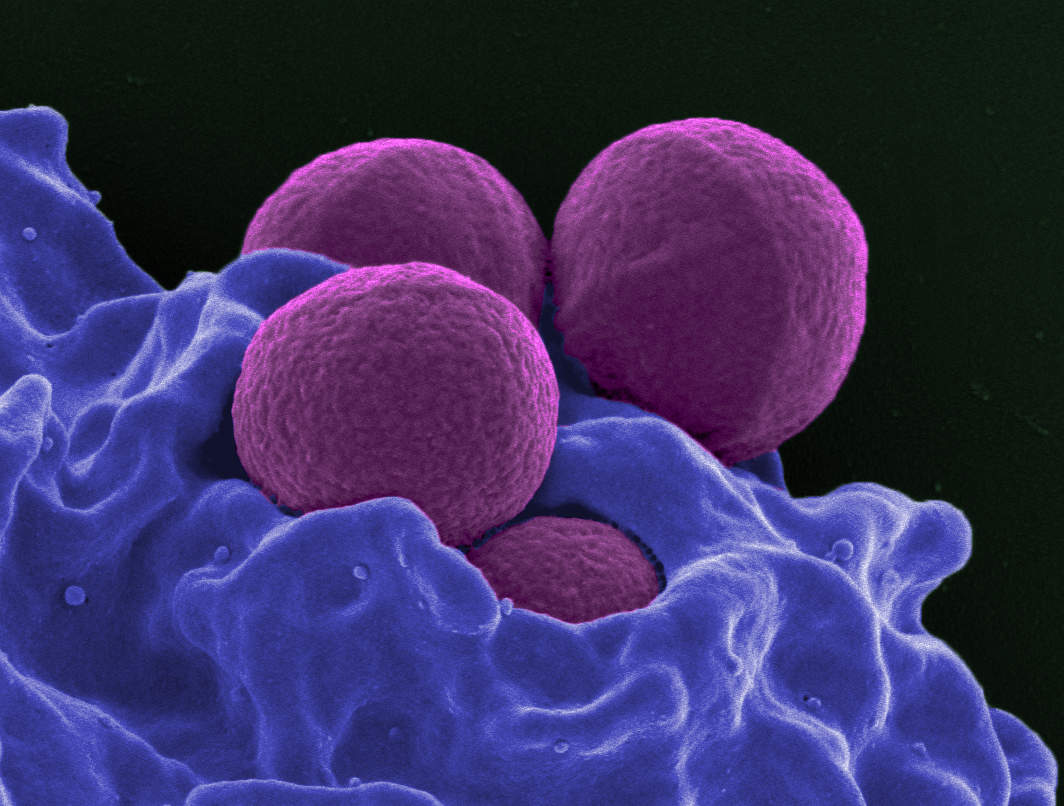

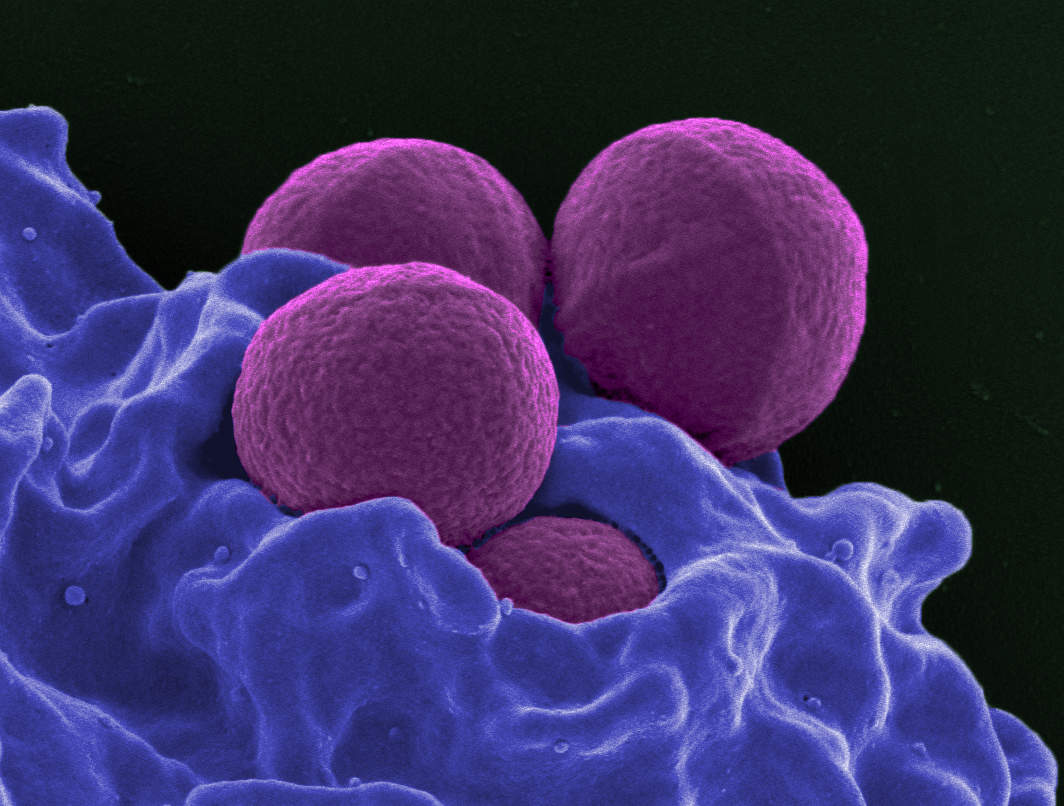

As resistance to antibiotics increases, we are at risk of returning to an era before Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin. That was the view of Mandeep Dhaliwal, director of health and HIV at the United Nations Development Programme, in an article for the Guardian newspaper last year. “We are on the road back to the days of people dying from common infections and injuries,” Dhaliwal said.

It might sound apocalyptic, but Dhaliwal’s doomsday scenario is backed up by a hefty body of research. According to The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, commissioned in 2014 by former UK Prime Minister David Cameron, ten million people a year could die across the world by 2050 if effective antibiotics are not found and manufactured.

The gold standard of business intelligence.

This is happening, says Kevin Outterson, executive director and head of CARB-X, because “unlike ever other drug class, antibiotics decline in effectiveness the more we use them. If somebody comes out with an amazing cancer drug or heart drug it will still work in five decades time. You can’t say the same for antibiotics.”

Despite an unprecedented need for new antibiotic drugs, companies are often hesitant to develop them. Resistance to antibiotics occurs when drugs are over-used and over-prescribed, creating a mismatch between public health officials who discourage this and companies who want to maximise their sales and revenues.

“The market is completely broken,” Outterson says. “If you had a lab with interesting new molecules for immuno-oncology there would be hundreds of people banging on your door to invest in it because there is a lot of money to be made. But nobody is making much money in antibiotics and the private market for pre-clinical research is therefore very thin.”

CARB-X was founded last year, in response to the US Government’s 2015 Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria initiative, with the goal of fixing this market failure. With a five-year funding pool of $155m, the organisation has quickly become the world’s largest public-private partnership devoted to early stage antibacterial research and development.

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Your download email will arrive shortly

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

“Before us, people were – so to speak – dying of thirst in the desert,” says Outterson. “Sometimes there would be small teams spun out of the university environment using money borrowed from friends and family. Sometimes there would be companies making money in other fields, investing a bit in antibiotics despite the poor economic return. Now with CARB-X we have the water: a substantial amount of capital that is essential for these projects to move forward.”

Much of CARB-X’s work involves tackling future threats, which Outterson, a professor of health law and corporate law at Boston University, compares to a country building military defence equipment.

“If you want to build an aircraft as a military asset you wouldn’t start doing it when you see incoming jets,” he says. “You have to build that aircraft carrier and begin the process a decade in advance. Similarly, today we see lots of bacteria in small numbers that are completely resistant to everything we have. They aren’t killing millions of people yet but they could do in the future.

“Starting from scratch, with a clever idea in a lab and taking it all the way to a new approved human drug takes at least a decade. So the challenge is not responding to today’s threats, it is responding to the threats that are harder to predict a decade or fifteen years in the future.”

To date, CARB-X has funded 18 projects. While Outterson has no favourite – “it’s like asking somebody which of their children they like the most”– he mentions the work of Indian biotech start-up, Bugworks Research, as particularly interesting. India is a country that has been especially badly affected by drug resistant infections over the past few years, including MRSA and E. coli.

“Bugworks is one of eight projects that we have that would, if successful, represent a new drug class against gram-negative bacteria,” Outterson explains. “To put that into perspective, the last gram-negative bacteria drug class that was approved by the US FDA was invented in 1962. Getting a new, gram-negative bacteria drug class would be spectacular.”

Two other projects, both located on the west coast of America, are attempting to inhibit LPX-C, an enzyme present in the outer membrane of certain types of bacteria. One of the companies involved, Achaogen, says its research “has the potential to treat infections due to multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, one of the drug-resistant bacteria on the World Health Organization’s top priority list.”

“LPX-C is a target that many drug developers have tried to tackle but it has been very difficult to get a drug approved,” says Outterson. “Nobody has ever successfully done an LPX-C antibiotic and so it has become the sort of thing large drug companies have just shied away from. These two companies are taking different approaches, and if one or both of them succeeds it will be momentous.”

A year after its creation, Outterson is amazed at how much interest CARB-X has managed to generate. “When we considered how many applications we might get, the expert consensus was 50 in the first year. But we got 368,” he says. “Our target was also to have five companies by the end of the first year but we’ve ended with 18.”

That success shouldn’t be surprising. The market may be faulty, but antibiotic resistance remains an exciting and profoundly important field to work in.

“I think most people would agree that antibiotics are the most critical drug class in human history in terms of how many lives they have saved,” Outterson says.