Simply fly long enough and you’ll eventually make a boneheaded or innocent mistake that gets in ATC’s way. Those may say a Pilot Deviation (PD) is where they “screwed up” or “ATC is blaming me for…” I’ve personally heard it put in many different—often creative—ways; I should keep a list.

Here is how the FAA defines it in FAA Order 8020.11D, “Aircraft Accident and Incident Notification, Investigation, and Reporting;” Chapter 1, “General Information;” Paragraph 7, Definitions: “Pilot Deviation (PD) – An action of a pilot that results in the violation of a Federal Aviation Regulation (FAR) or a North American Aerospace Defense (Command Air Defense Identification Zone) tolerance.”

How does this compare to what ATC might say on frequency? The definition above wouldn’t be issued by a controller, as we are not the ones to say if you did something wrong or not. Despite seeing a direct violation to instructions, our saving grace is saying the word “possible.” Notice of a “possible” PD is also referred to as the “Brasher Warning.” The name comes from Captain Jack Brasher who, in 1985, busted an altitude but didn’t get the warning from ATC, although it was part of their procedures. On appeal, the NTSB upheld the violation but overturned Brasher’s certificate suspension.

You might wish to review the excellent article by Mark Kolber in July, “Dude! You’re Busted!” in which he explains the formal process. My intent here is to give you the controller’s side of the process.

Possible Pilot Deviation

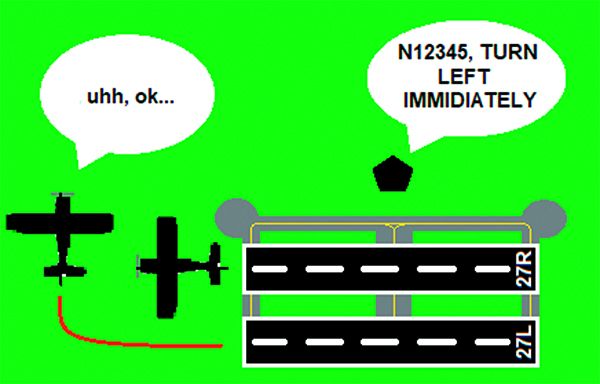

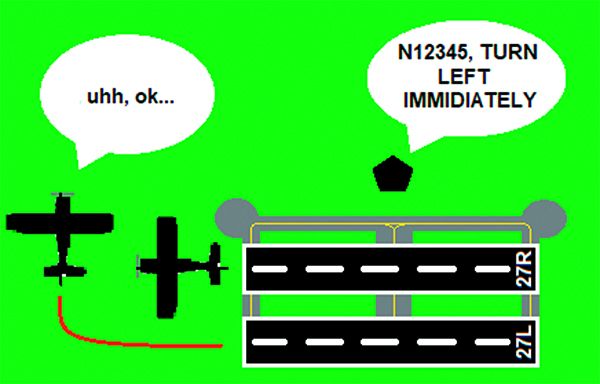

Imagine you’re the PIC, departing from Runway 27L. Tower: “N12345, I’ll call your right turn north east. Runway 27L, cleared for takeoff.” You respond appropriately. Maybe on a subconscious level, you realize that there are departures off of Runway 27R as well. You rotate and climb, and Tower tells you, “N12345, make it a left turnout; left turnout approved.”

It passes right through your mind and you respond correctly verbally, but not physically, as you start a turn to the right, into departures off 27R. Tower catches you in time and tells you to turn left immediately. While your mind is racing to catch up, you comply and make that left turn. Crisis averted, now what? You get that dreaded call, “N12345 advise you have a pen and paper.” This is where the fun begins.

The right—and wrong—way to respond to a deviation should be common sense. A simple, “ready to copy” and professional response goes a long way on a recorded frequency. If you’re contemplating anything other than that, you should be thinking, “Anything you say can and will be used against you.” I’ve had my share of both. If you are in a critical phase of flight, controllers generally understand that we might not get a response at that moment, or merely get a “standby.”

Sometimes, your goof can cause some real controller headaches or, worse, possibly a near miss. Everyone gets their adrenalin going in those situations and occasionally a controller can get wound up from the stress and starts badgering on frequency. If that happens to you, it’s best to keep your cool, remain compliant, and just ask ATC to “Mark the tapes” while making a note of the time. At times like those, it’s common for everyone to think the other guy goofed, and only the investigation will reveal the truth.

Most controllers work in a radar room without windows. Even in the tower, I don’t always have the best view to see exactly what happened. Either way, my job is to sequence and separate the traffic, not find deviations.

Nonetheless, for example, if I see you cross the hold-short line after acknowledging my hold-short instruction with someone on short final, in my mind you definitely screwed up. My tone on the frequency will often become more stern, but I’ll keep my composure while saying, “Possible pilot deviation—advise you contact (ATC Facility) at (number).”

Have you ever tried to run from the cops? Probably not. While ATC are not the sky police, we do report potential deviations. Trying to get out of these is ill-advised. Even if you turn your transponder off, you can still be tracked with a simple “tag” on your primary radar return.

At most facilities, any airplane who appears to commit an infraction and is not “talking to anyone” (Class B or D violators mainly) can get tagged as a “VIOL8R” and followed to their destination. With the upgrade to the required ADS-B, most facilities have the capability to click on your target and see your full call sign. That along with FlightAware and other resources makes it near impossible to try to “run” from getting deviated. Unless you are flying an F-22 in stealth mode, I recommend against it.

JO 7210.632. Air Traffic Organization Occurrence Reporting3-1. Flight Crew Notification of Suspected Pilot Deviations (PD)

a. When the employee providing air traffic services determines that pilot actions affected the safety of operations, the employee must report through the MOR process and notify the flight crew as soon as operationally practical using the following phraseology:

PHRASEOLOGY-

(Aircraft identification) POSSIBLE PILOT DEVIATION, ADVISE YOU CONTACT (facility) AT (telephone number).

b. The employee reporting the occurrence should notify the front-line manager (or controller-in-charge), operations manager, as appropriate, of the circumstances involved so that they may be communicated to the pilot upon contacting the facility.

NOTE-

This notification, known as the “Brasher Notification,” is intended to provide the involved flight crew with an opportunity to make note of the occurrence and collect their thoughts for future coordination with Flight Standards regarding enforcement actions or operator training.

After You Land…

After ATC issues a possible PD over the radio, there a few steps that we have to take as well. Depending on the event, controllers might even be asked for an official statement.

The first thing we do after a Brasher notification is start writing an MOR (Mandatory Occurrence Report). It’s basically a report on what appeared to happen on the ATC side of things, with call signs, locations, frequencies, etc. The MOR is the go-to form for anything out of the ordinary in an ATC environment. Depending on staffing and traffic workload, we could possibly have this report done by the time the pilot calls (if they do). When the pilot lands and after safely securing the airplane and other items as required, it is expected that they call.

Next, do you make that call? It has been argued that a pilot is not even required to call for a few reasons, but be prepared either way. If you have an audio or, better yet, video recording of the flight, review it. When you call, I highly recommend that you confidently understand what happened to the best of your memory.

The phone lines to our facilities are recorded, just like our radios. Choose your words knowing that you’re being recorded, so keep it calm and reasonable.

Depending on your attitude and what you say, that call could rapidly digress from a simple inquiry or clarification, to a near-criminal interrogation. Be careful what you say and how you say it.

ATC will probably tell you what they “appeared” to see and ask why it was done, and you have the choice to respond or not. Again, this conversation could be referenced by FSDO when or if the time comes. In these calls, a cooperative, learning attitude is your best friend. A nice conversation between ATC and pilots is always welcome, even in these instances. With a little luck, if the situation wasn’t too serious to begin with, at the end of the conversation you might simply get, “Have a nice day. Fly safe.” You’re done.

If you want to explore more resources before making the call, you may. Whether you make the call or not, my strongest recommendation is that you fill out a NASA ASRS report. AOPA has a few resources that can be accessed in these situations as well. Keeping things cordial, I’ve seen deviated pilots ask for tours on that call, and almost all of the time, the response was, “When can you be here? Happy to do it!”

Even though it’s not mandatory, I would urge you to make the call at least to close the loop. If you’re not prepared to discuss the incident, merely say so. You’ll be asked for identifying information (name, certificate number, tail number, etc.). Then add, “I wanted to be responsive and make this call, but I’m not prepared to discuss any particulars of the event until I’ve had a chance for further review.”

First Time For EverythingA few months ago, I was working Tower, and for a short period had absolutely nothing going on. Times like this, I normally do a few laps around the tower cab to stay active.

As I was taking a few laps and watching my Class D surface area, out of nowhere a helicopter shows up just two miles north of the field. I asked the ground controller where it came from,. She replied, “I’ve no idea. It wasn’t even on the radar until just now.” So, I looked with my binoculars and called on the radio, “Aircraft operating two miles north of the airport, say call sign.” No response. I transmitted about 15 times while the helicopter came all the way to a very short downwind, circled, then turned back away a couple miles.

I was so glad there was no other traffic. Imagine if there’d been students in the pattern. Finally, he called, “Tower, Helicopter 12345, two north. Inbound for pattern work.” Thankfully, what went through my head never came out of my mouth. “N12345, Tower, you have been in my airspace for five minutes. I’ve been calling you. Did you hear my calls?” Pilot replied, “Sorry tower. We were on the wrong frequency.” “N12345, make approach straight in, taxiway echo. Cleared to land.” I continued to work him in the pattern until he landed and called. Seems he didn’t pop up on the tower radar display because he was below 200 feet AGL at the time. Because of my concern over the potential safety issues, I decided to deviate him.

The pilot explained he’d been on the wrong frequency. I explained what could have happened with a pattern full of … anything, but particularly students. He was contrite and hadn’t been deviated in 40 years of flying. After I copied down his information, he asked, “what happens now?” I told him to file a NASA report and that FSDO might contact him to go over the incident and actions taken to prevent it from occurring again. I finished with, “I wouldn’t worry about the FSDO too much, but do whatever you need to fly safe!”—EH

Learn and Improve

After the initial impact has passed, you could get a call from our friends at the Flight Standards District Office, FSDO. It is really not a big deal. FSDO can choose to take the MOR data, and listen to the recordings to get a better picture before talking with you. In limited cases, they have called ATC facilities for more info, and possibly the statement I mentioned above. I’ve had friends that have been called by them for deviations and non-deviation items as well.

They, like everyone, are just doing their job and following up as required. It is (hopefully) just a pleasant conversation about the event that occurred and your thoughts on what was reported. But, penalties for significant infractions can include certificate action, a 709 check ride, or civil penalties. A “709 Ride” is basically a re-check ride completed by a FSDO examiner. Whenever I’m on that initial call with the pilot involved, they think that it’s like getting pulled over by the sky police, which is not our intent at all. We just report. FSDO will take action, if appropriate.

A PD by itself isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Enough PDs along with NASA reports in a certain area and for certain reasons ignites a “trend.” Trending items are thoroughly investigated by a team of controllers, safety experts, pilots, etc. It could lead to systemic changes either in an ATC environment, or within an airspace environment.

For example, if there is a Class D airport with a high hill on one side of the base to a runway, and pilots keep overshooting or experiencing a “runway illusion,” this could lead pilots to misjudge things, which in turn could affect their flying. If you called “traffic to follow in sight” yet turned right into them, you could be deviated.

Perhaps there’s a controller who has a short temper, loves paperwork and they deviate even trivial errors. (Rare and highly discouraged, but they exist.) Regardless of the root cause, that team will investigate and recommend the best solution. For the hill, there might be a change to the recommended traffic flow. The heavy-handed controller might get some “counseling.”

Note that a deviation is not needed for a pilot to file a NASA report. Enough NASA reports at the imaginary airport above might lead to a change in procedures without any pilot deviations. That form is a powerful tool for pilots and controllers, and it only takes a few minutes to complete.

From “possible pilot deviation” until after FSDO calls, what do pilots and controllers take away from these? Probably at least some introspection, experience, training, and perhaps a little wisdom. We all keep learning.

Sometimes you get deviated for something and other times you don’t. It depends on the controller, the day of the week, traffic load, etc. But the controller will likely tell you something like, “Don’t do that again” or “N12345, you were told to do (this) and you did (that). Fly heading 360…” What do you take away from these events, or even hearing someone else get chastised? You get the same things: introspection, experience, training, and perhaps a little wisdom.

Moving Forward

No one is “out to get you” and ATC are not the police. Handling a deviation correctly and humbly will minimize the chances of getting violated. While there is potential for some punitive consequences, we should all continue to move forward and learn.

Elim Hawkins dislikes giving deviations as much as pilots dislike receiving them and offers this advice: “Y’all be good now, ya hear?